The Most Human Feature May Be the Least Purposeful

Look in the mirror and you will see something that no other animal on Earth possesses: a chin. That bony protrusion at the base of your lower jaw is uniquely human, absent in every other primate and indeed every other species alive or extinct. For over a century, scientists have debated why we have chins and what evolutionary advantage they might confer. A new study proposes a surprising answer: the human chin is not an adaptation at all. It is a happy accident, a structural byproduct of other evolutionary changes to the human face that conferred no direct survival benefit of its own.

The finding challenges the long-standing assumption that every prominent anatomical feature must have been shaped by natural selection for a specific purpose. Sometimes, the researchers argue, evolution produces features that are simply along for the ride.

A Century of Chin Theories

The chin has been a source of scientific fascination and frustration since at least the early twentieth century. Its uniqueness among primates is striking. Chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, have receding lower jaws with no hint of a chin. Neanderthals, who were in many respects physically robust, also lacked chins. Even early members of our own species, Homo sapiens, from 300,000 years ago had only weakly developed chins compared to modern humans.

Over the decades, numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain the chin's existence, each attempting to identify a selective advantage that would justify its evolution:

- Mechanical reinforcement: The most popular hypothesis held that the chin strengthens the lower jaw against the stresses of chewing. This seemed intuitive, as the chin bone is positioned where bending forces during mastication are highest.

- Speech adaptation: Some researchers proposed that the chin helps anchor the muscles involved in human speech, a function not required in other primates.

- Sexual selection: Others suggested that the chin evolved as a signal of mate quality, with a prominent chin indicating good health or genetic fitness.

- Resistance to tongue forces: The unique human practice of swallowing food in a specific pattern generates forces that might require additional jawbone support.

Each of these hypotheses has attracted supporters and critics, but none has achieved consensus. The new study explains why: they may all be looking for an answer to the wrong question.

The Byproduct Hypothesis

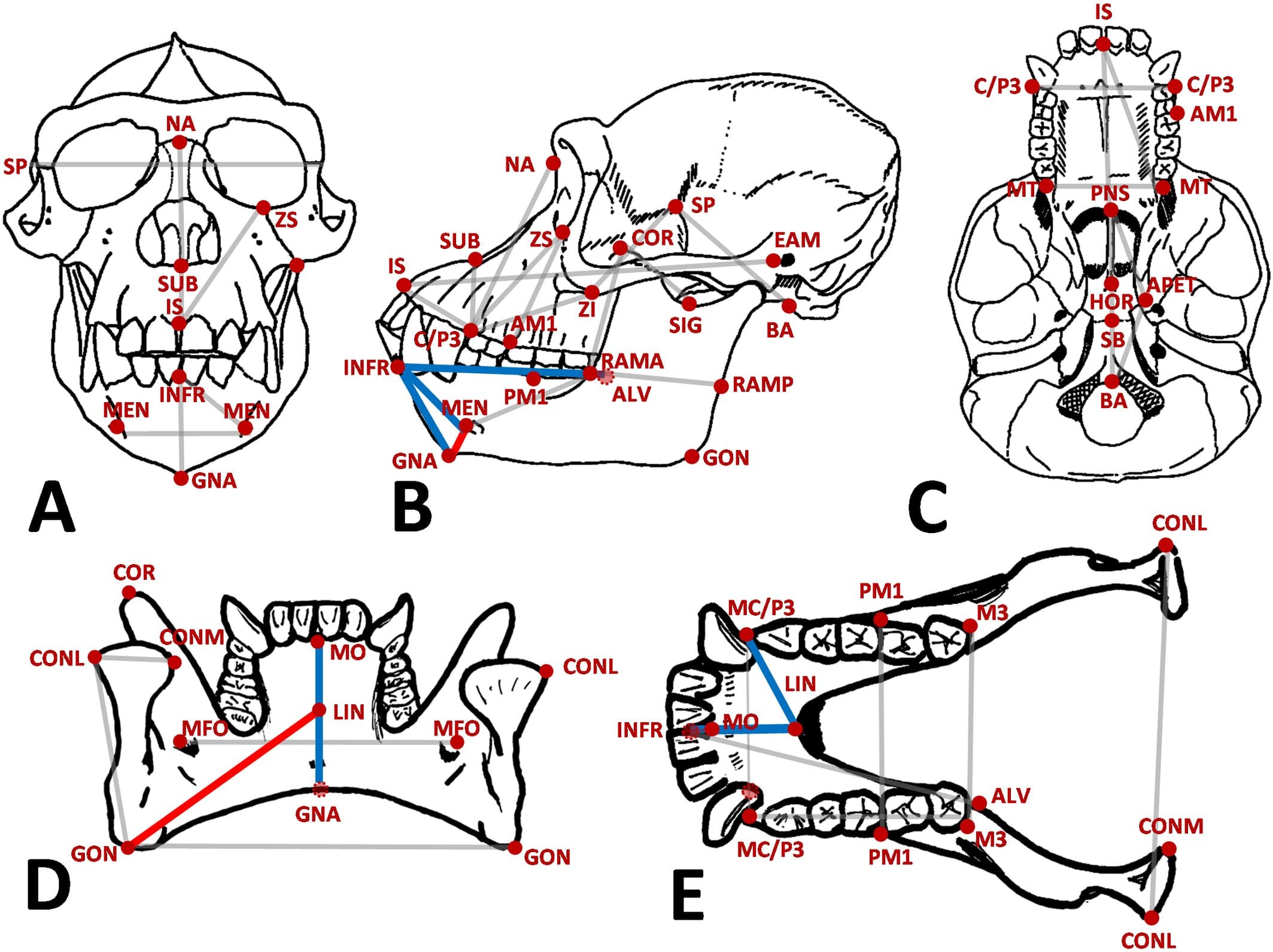

The research team approached the chin problem from a different angle. Rather than asking what the chin is for, they asked how the chin came to be. Using a combination of CT scanning, geometric morphometrics, and computational biomechanical modeling, they analyzed the skulls of modern humans, Neanderthals, and several earlier hominin species to track how the lower jaw changed over the course of human evolution.

Their analysis revealed that the chin is not a structure that was added to the jaw. Rather, it is what remained after other parts of the jaw were reduced. Over the past several hundred thousand years, the human face has undergone a dramatic process of reduction. Our brow ridges have shrunk, our upper jaw has pulled back, our teeth have become smaller, and our lower jaw has shortened and narrowed.

These changes were driven by well-documented evolutionary pressures, including the adoption of cooking, which reduced the need for large teeth and powerful chewing muscles, and possible selection for less aggressive-looking faces, which promoted social cooperation.

As the rest of the jaw shrank, the base of the lower jaw, the region that forms the chin, did not shrink at the same rate. The result is a relative projection that we perceive as a chin, even though nothing was actually added. The chin is what you get when you subtract the rest of the jaw.

The Biomechanical Evidence

To test this hypothesis, the team conducted finite element analysis, an engineering technique that models how forces distribute through complex structures. They built detailed computer models of lower jaws at various stages of human evolution and subjected them to simulated chewing forces.

If the mechanical reinforcement hypothesis were correct, the chin region should experience high stresses during chewing that the chin bone helps to resist. But the models showed the opposite. The chin region experiences relatively low stresses during normal chewing, and removing the chin from the model had minimal effect on the jaw's overall structural integrity.

Furthermore, the team found that the evolutionary reduction of the jaw actually improved its biomechanical efficiency. Smaller jaws with smaller teeth require less force to operate, and the muscles that drive them can be positioned more effectively. The chin is not needed for mechanical support because the lighter, more efficient jaw simply does not generate the forces that would require it.

What About Speech?

The speech hypothesis also failed to find support in the new analysis. The muscles involved in speech, particularly the genioglossus, which controls tongue movement, do attach to the chin region. However, the team showed that these muscles are adequately anchored by the bone present in chinless jaws as well. Neanderthals, who likely had some capacity for complex vocalization despite lacking chins, provide a natural test case: speech muscles do not require a chin.

The sexual selection hypothesis is harder to rule out definitively, as preferences for facial features are notoriously difficult to study in an evolutionary context. However, the team argues that sexual selection for chin prominence is unlikely to be a primary driver because the chin emerged gradually as part of a broader pattern of facial reduction rather than appearing suddenly as a new and distinctive feature.

Spandrels and Evolutionary Byproducts

The concept of an evolutionary byproduct is not new. In 1979, evolutionary biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin published a famous paper arguing that not every biological feature is an adaptation shaped by natural selection. Some features, which they called spandrels after the triangular spaces created by arches in architecture, arise as structural consequences of other changes and persist because they do no harm.

The chin appears to be a textbook spandrel. It emerged as a geometric consequence of jaw reduction, and because it imposed no fitness cost, natural selection had no reason to eliminate it. Over time, cultural associations may have developed around chin shape and prominence, but these are likely consequences rather than causes of the feature's existence.

This interpretation has broader implications for how we think about human evolution. The temptation to construct adaptive stories for every human feature, from earlobes to belly buttons to chins, can lead researchers down unproductive paths. Sometimes the most parsimonious explanation is that a feature simply happened, a byproduct of changes elsewhere in the organism.

Implications for Paleoanthropology

The chin has long been used as a taxonomic marker in paleoanthropology. The presence or absence of a chin is one of the criteria used to classify fossil specimens as anatomically modern Homo sapiens. The new research suggests this practice should be applied with caution.

If the chin is a byproduct of facial reduction rather than a discrete adaptation, its development likely varied among early modern human populations depending on the degree and pace of facial reduction they experienced. Using chin presence as a binary criterion for modernity could lead to misclassifications, particularly for specimens from the transitional period when modern human facial proportions were still evolving.

The study also provides a new lens for understanding variation in chin morphology among living humans. Chin shape varies considerably across populations and individuals, and this variation may reflect underlying differences in the pace and pattern of facial reduction rather than selection for chin-specific functions.

The Beauty of Accidental Anatomy

There is something oddly satisfying about the conclusion that one of our most distinctively human features is an evolutionary accident. It serves as a reminder that evolution is not a purposeful designer working toward a goal. It is a blind process that tinkers with existing structures under the pressure of survival and reproduction, and sometimes the tinkering produces features that persist not because they are useful but simply because they are not harmful enough to be eliminated.

The human chin, that small but unmistakable projection of bone, is a monument to the contingency of evolution. It tells us not what we were selected to become, but what happened to be left over after everything else changed.