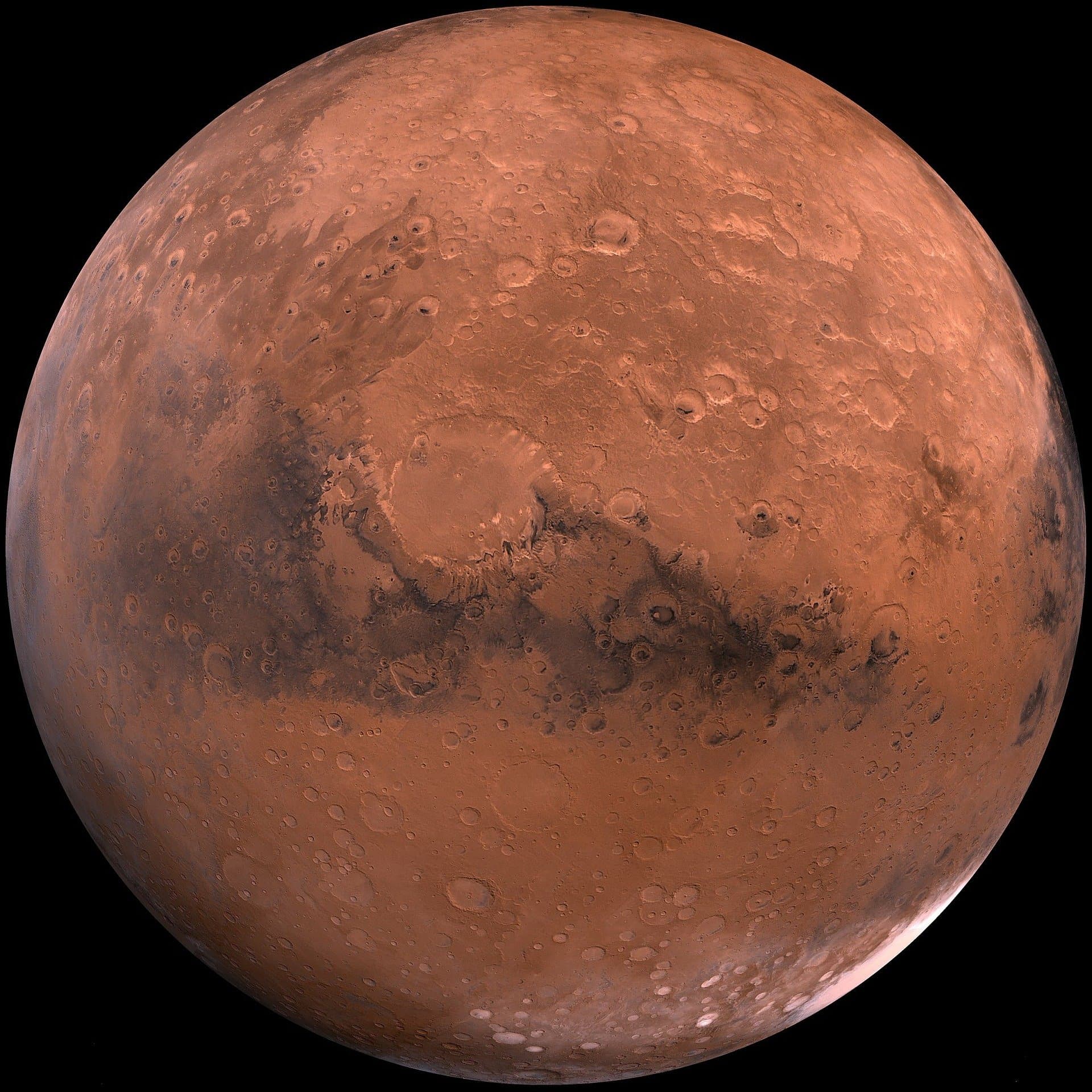

Rewriting the Story of Martian Volcanism

For decades, planetary scientists treated many of Mars' smaller, younger volcanoes as geologically simple features, each the product of a single eruption that punched through the crust and went quiet. New research published in Geology overturns that assumption. By combining high-resolution orbital mapping with mineral spectral analysis, an international team led by Bartosz Pieterek of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan has shown that at least one young volcanic system south of Pavonis Mons experienced a far more intricate eruptive history than anyone expected.

Reading Minerals From Orbit

The team used data from orbiting spectrometers to identify distinct mineral signatures in the surface lava flows around the volcanic complex. Different minerals crystallize at different temperatures and pressures, so their presence on the surface acts as a chemical fingerprint of the conditions deep underground where the magma formed and evolved.

What the researchers found was not a single mineral signature, as would be expected from one eruption of uniform magma, but several distinct compositions layered across the volcanic edifice. Each composition corresponds to a different phase of magmatic activity, indicating that the subsurface plumbing system changed character over time.

"The volcano did not erupt just once. It evolved over time as conditions in the subsurface changed," Pieterek explains. "What appears to be a single volcanic event is often the result of complex processes operating deep beneath the surface, where magma moves, evolves, and changes over long periods."

Evidence of Magmatic Differentiation

The paper presents spectral evidence for magmatic differentiation, a process in which a body of molten rock changes composition as minerals crystallize and settle out or as fresh magma intrudes from below. On Earth, differentiation is well documented in long-lived volcanic systems such as Yellowstone and Mount Etna. Finding clear signs of it on Mars suggests that the Red Planet's interior remained thermally active enough to sustain evolving magma chambers far more recently than the canonical timeline implied.

Implications for Mars' Thermal History

Mars is roughly half the diameter of Earth and was long thought to have cooled rapidly, shutting down most volcanic activity billions of years ago. The Tharsis region, home to Olympus Mons and the Pavonis Mons chain, is the notable exception, with some lava flows dated to within the last few hundred million years. Even these, however, were generally seen as the dying gasps of a cooling planet.

The new findings complicate that narrative. If young volcanoes hosted long-lived, evolving magma systems, then Mars' interior retained enough heat and fluidity to support complex magmatic processes much more recently than simple cooling models predict. This has implications for the planet's geodynamic history, for the possibility of residual geothermal activity, and for the habitability of the subsurface.

A Template for Future Exploration

The study also demonstrates the power of orbital mineral spectroscopy as a tool for planetary geology. Without setting foot on the surface, the team was able to reconstruct a multi-phase volcanic history that would rival the complexity of many terrestrial field studies. As next-generation orbiters and eventually human explorers reach Mars, the mineral maps produced by this work can guide sample-collection campaigns to the most scientifically valuable sites.

Pieterek's team plans to apply the same analytical approach to other young volcanic fields across Mars, testing whether multi-phase eruptive histories are the exception or the rule. If complexity turns out to be widespread, the textbook picture of Martian volcanism as simple, monotonic, and moribund will need a thorough rewrite.