The Mystery of the Human Chin

Look in a mirror and you will see something no other primate possesses: a chin. Chimpanzees do not have one. Gorillas do not have one. Neanderthals, Denisovans, and every other extinct member of the human family tree lacked a protruding bony shelf at the base of the lower jaw. Only Homo sapiens walks around with this peculiar anatomical feature, and for more than a century, scientists have argued about why.

A new study led by Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel, professor and chair of anthropology at the University at Buffalo, offers a provocative answer: the chin is not an adaptation at all. It is an evolutionary accident, a structural byproduct of changes elsewhere in the skull. The findings appear in PLOS One.

Testing the Null Hypothesis

Previous explanations for the chin have invoked everything from speech mechanics to sexual selection to resistance against chewing stress. Each hypothesis assumes that natural selection actively favored a protruding chin, shaping it over thousands of generations because it provided some survival or reproductive advantage.

Von Cramon-Taubadel's team took the opposite approach. Rather than looking for evidence of selection, they tested the null hypothesis: that the chin could have arisen through neutral evolutionary processes, as an unselected consequence of changes in surrounding skeletal structures.

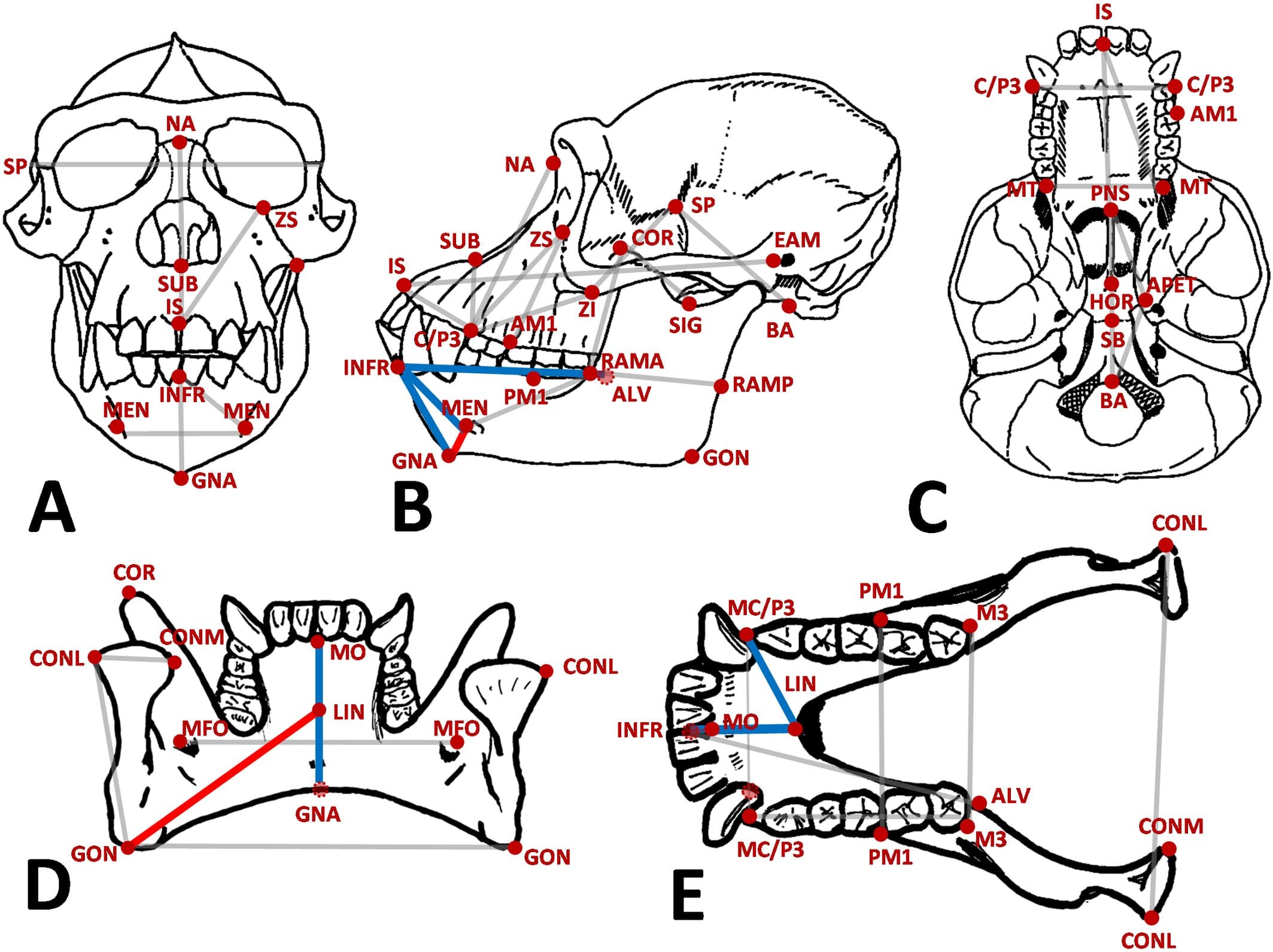

The researchers compared cranial and mandibular measurements across apes and humans, analyzing whether the evolutionary changes in the chin region align better with the signature of natural selection or with the random drift expected from a trait that is merely along for the ride.

Spandrels in Biology

The concept draws on an influential idea from the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who borrowed the architectural term "spandrel" to describe biological structures that exist not because they were designed for a purpose but because they are inevitable geometric consequences of building something else. The triangular spaces beneath the arches in a cathedral are spandrels: they are not there for decoration, even though artists later filled them with mosaics. They exist because arches must meet walls.

Von Cramon-Taubadel argues the chin is a biological spandrel. As the human face shortened and retracted over evolutionary time, driven by shifts in diet, cooking technology, and brain expansion, the lower jaw remodeled in ways that left a protruding bony ridge at the front. The chin was not the target of selection. It was the leftover.

Why the Distinction Matters

The difference between an adaptation and a spandrel is not merely academic. Assuming that every anatomical feature was shaped by selection leads to "just so" stories, plausible-sounding but untestable narratives about ancestral environments. These stories can distort our understanding of human evolution by attributing purpose to structures that have none.

"Within anthropology, there is an adaptationist bent in how people view physical characteristics," von Cramon-Taubadel explains. "Observed differences between species can contribute to the assumption that all characteristics have been deliberately shaped over time, which suggests purpose or function."

By rigorously testing the spandrel hypothesis, the study provides a methodological template for evaluating other uniquely human traits. Features such as the white sclera of the eye, the shape of the external ear, or the arch of the foot may also deserve the same scrutiny: are they adaptations, or are they architectural consequences of changes elsewhere?

Rethinking Human Uniqueness

The chin has long been held up as a marker of modernity, one of the features that distinguish anatomically modern humans from archaic relatives. If it is indeed a spandrel, then its presence in the fossil record says less about what our ancestors could do, speak, chew, or attract mates, and more about how their skulls happened to be built.

That is a humbling conclusion, but it is also a clarifying one. Evolution is not an engineer with a blueprint. It is a tinkerer constrained by physics, geometry, and history. Sometimes the most distinctive feature on a face is simply the space left over when everything else moved.