When Biology Meets Liquid Crystal Physics

Every time a human cell divides, thousands of protein filaments called microtubules assemble into a football-shaped spindle that pulls chromosomes apart with remarkable precision. How this intricate machine builds itself without an external blueprint has been one of cell biology's most persistent questions. A new study now provides a compelling answer: the spindle self-organizes according to the same physics that governs liquid crystals in display screens.

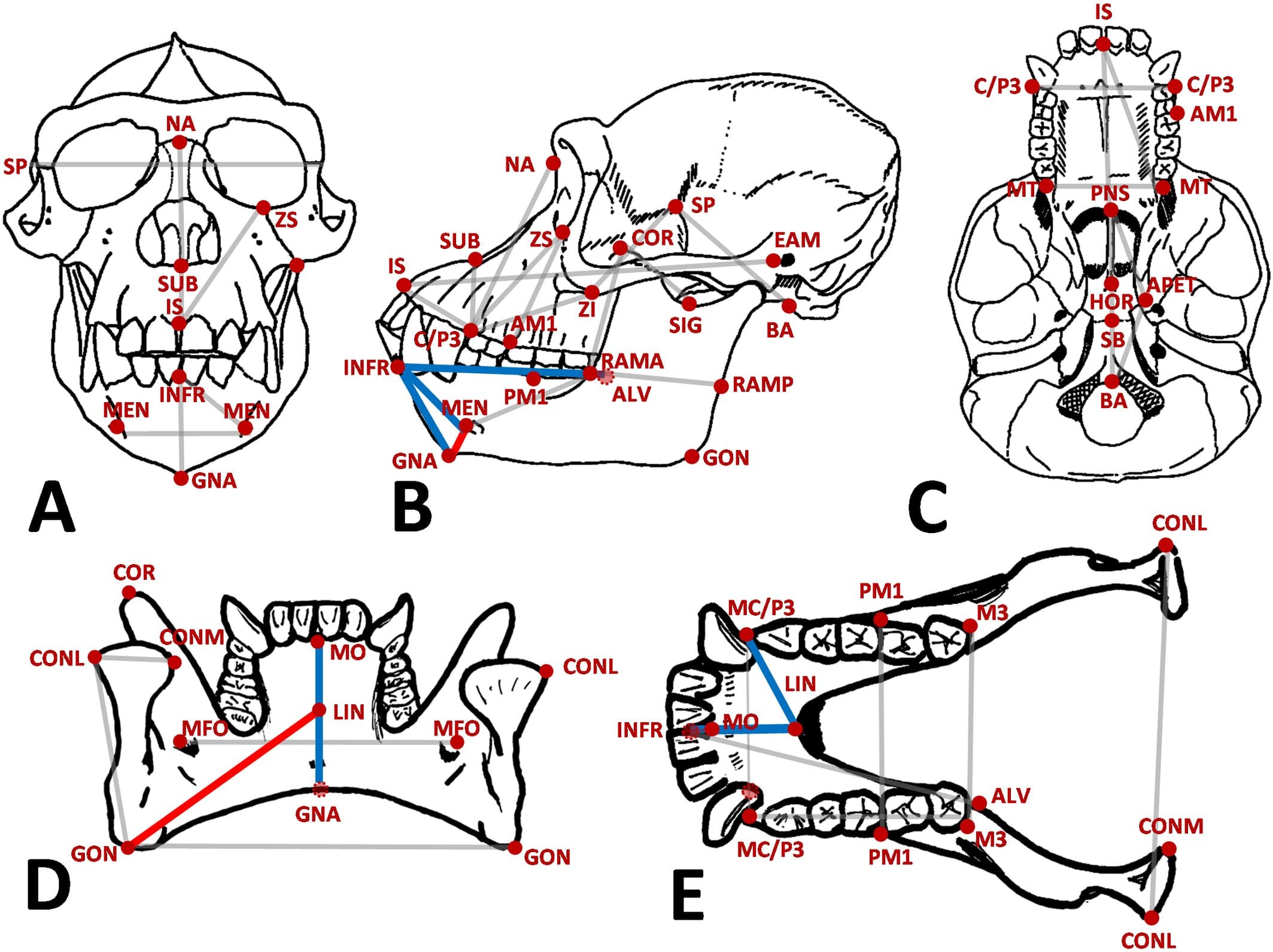

The research, which combines electron tomography reconstructions with polarized light microscopy, tested an active liquid crystal continuum model against real measurements of human mitotic spindles. The predictions of this coarse-grained theory quantitatively matched the experimentally observed spindle shape, microtubule orientation, density patterns, and fluctuation spectra, confirming that a handful of physical parameters can explain the collective behavior of tens of thousands of molecular components.

What Are Active Liquid Crystals?

Conventional liquid crystals, the kind in smartphone screens, consist of rod-shaped molecules that align with one another while remaining fluid. Active liquid crystals add a twist: each rod consumes energy and generates force. Microtubules fit this description perfectly. Powered by molecular motors and GTP hydrolysis, they continuously grow, shrink, slide, and pivot, creating a material that is simultaneously ordered and restless.

The theoretical framework treats the spindle as a nematic active liquid crystal, meaning that the microtubules tend to align along a common axis but do not all point in the same direction. The model captures three key behaviors: collective co-alignment, where nearby microtubules nudge each other into parallel arrangements; diffusion, where random thermal and motor-driven forces spread microtubules laterally; and polar transport, where motor proteins slide antiparallel microtubules apart to shape the spindle's tapered ends.

From Microscopic Interactions to Mesoscale Structure

One of the study's most powerful results is the ability to infer material properties from imaging data. By fitting the model to experimental spindle shapes and fluctuation patterns, the researchers extracted values for nematic elasticity, microtubule diffusivity, and turnover dynamics. These numbers provide a quantitative link between the molecular-scale interactions of individual microtubules and the emergent mesoscale architecture of the entire spindle.

Why It Matters for Medicine

Errors in spindle assembly are a hallmark of cancer. Tumor cells frequently produce misshapen spindles that segregate chromosomes unevenly, driving the genomic instability that fuels tumor evolution. If the spindle truly obeys liquid crystal physics, then its failure modes should also follow predictable patterns.

Anticancer drugs such as taxanes and vinca alkaloids already target microtubules, but their effects on spindle-scale organization remain poorly understood. The liquid crystal framework could help predict how changing a single molecular parameter, such as microtubule stability or motor speed, propagates upward to distort the entire structure. This top-down understanding might guide the design of more selective therapies that disrupt cancer-cell spindles while sparing healthy ones.

A Universal Organizing Principle

The implications extend beyond cell division. Microtubule-based structures appear throughout biology, from the cilia that sweep mucus out of lungs to the axons that wire the brain. If the same active liquid crystal physics applies to these systems, it could unify a wide range of biological self-organization phenomena under a single theoretical umbrella.

The study also demonstrates the power of coarse-grained modeling in biology. Rather than simulating every molecular interaction, the liquid crystal approach captures the essential physics with a small number of equations. This efficiency makes it possible to explore parameter space quickly, generating testable predictions that experiments can confirm or refute.

Looking Ahead

The research team plans to extend the model to meiotic spindles, which divide chromosomes during the production of eggs and sperm, and to spindles in organisms with very different cell sizes. If the theory holds across these contexts, it will cement active liquid crystal physics as a foundational principle of biological architecture, a bridge between the randomness of molecular motion and the order of living structure.