Artificial Intelligence Takes on One of Nature's Most Destructive Forces

Flooding is the most costly natural disaster in the United States, causing billions of dollars in damage and claiming dozens of lives every year. Despite massive investments in forecasting infrastructure, existing flood prediction systems remain frustratingly imprecise, often providing warnings that are too late, too vague, or too localized to enable effective emergency response. Now, a new artificial intelligence framework promises to change that equation fundamentally, delivering flood predictions that are faster, more accurate, and more comprehensive than anything currently available.

The framework, developed by a consortium of hydrologists, computer scientists, and climate researchers, represents a paradigm shift in how flood forecasting is approached. Rather than modeling individual river basins in isolation, the system treats the entire national river network as an interconnected system, using deep learning to capture the complex dependencies between upstream and downstream locations that traditional physics-based models struggle to represent.

How the AI Framework Works

At its core, the system is built on a specialized neural network architecture designed to process spatiotemporal data across vast geographic scales. The model ingests a continuous stream of inputs including real-time precipitation measurements from weather radar and rain gauges, satellite-derived soil moisture estimates, snowpack observations, river gauge readings, topographic data, and land use classifications.

What makes this framework distinctive is its ability to learn the hydrological relationships between thousands of river segments simultaneously. Traditional models require separate calibration for each watershed, a time-consuming process that often results in poor performance in ungauged basins where historical data is sparse. The AI framework, by contrast, learns general hydrological principles from data-rich basins and transfers that knowledge to data-poor regions.

The Architecture: Graph Neural Networks Meet Transformers

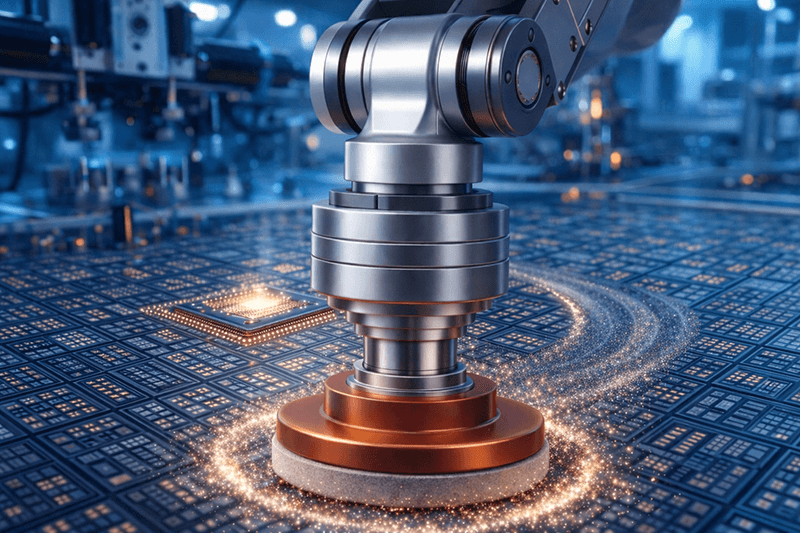

The technical architecture combines two cutting-edge approaches from machine learning. A graph neural network represents the river network as a connected graph, where each node is a river segment and edges represent the flow connections between them. This allows the model to explicitly account for how water moves through the network, propagating flood waves from upstream tributaries to downstream main stems.

Layered on top of the graph network is a temporal transformer, an attention-based architecture that processes the time series of observations at each location. The transformer component excels at capturing long-range temporal dependencies, such as the delayed effect of snowmelt on river flows weeks later, or the impact of antecedent soil moisture conditions on flood magnitude.

Together, these components create a model that reasons about both spatial connectivity and temporal dynamics, two aspects of flood prediction that traditional approaches have struggled to handle simultaneously.

- Spatial coverage: Over 2.7 million river segments across the continental United States.

- Temporal resolution: Hourly predictions updated every six hours as new observations arrive.

- Forecast horizon: Up to 10 days for major river systems, 3 to 5 days for smaller watersheds.

- Training data: 40 years of historical observations from over 8,000 stream gauges.

Performance That Outstrips Traditional Models

In extensive benchmarking against the current operational National Water Model, the AI framework demonstrated substantial improvements across virtually every performance metric. For flood events specifically defined as flows exceeding the 95th percentile at a given location, the AI system achieved a hit rate of 89 percent compared to 72 percent for the physics-based model, while simultaneously reducing false alarms by 35 percent.

Perhaps more impressively, the AI framework showed its greatest improvements in precisely the situations where accurate forecasts matter most: extreme events and ungauged locations. For the top one percent of flood events, the most severe and damaging, the AI system's predictions were on average 40 percent more accurate than the traditional model. And in ungauged basins, where physics-based models must rely on parameter estimation rather than calibration, the AI framework's advantage was even larger.

Speed and Computational Efficiency

The computational advantages are equally striking. The current National Water Model requires substantial supercomputing resources to generate a single forecast cycle, with run times measured in hours. The AI framework, once trained, can generate predictions for the entire continental river network in under 10 minutes on a single high-end GPU server.

This speed advantage is not merely a matter of convenience. In rapidly evolving flood situations, the ability to generate updated forecasts quickly can mean the difference between timely evacuation orders and devastating loss of life. The AI framework's fast inference time also enables ensemble forecasting, running hundreds of slightly varied predictions to quantify uncertainty, something that is computationally prohibitive with traditional models.

Addressing the Trust Problem

One of the most significant barriers to adopting AI in operational forecasting is the trust deficit. Forecasters and emergency managers are understandably reluctant to base life-and-death decisions on models they cannot understand or interrogate. The development team has addressed this concern through several deliberate design choices.

First, the model's graph neural network architecture is inherently interpretable in its spatial reasoning. Forecasters can trace which upstream locations contributed most to a given downstream prediction, matching their physical intuition about how water moves through the network.

Second, the team developed an attention visualization tool that highlights which historical time periods the temporal transformer is focusing on when making a prediction. This allows forecasters to verify that the model is attending to physically relevant precursors such as recent heavy precipitation or elevated soil moisture rather than spurious correlations.

Third, the system provides calibrated uncertainty estimates with every prediction, giving forecasters a quantitative measure of confidence that they can incorporate into their decision-making process.

The Path to Operational Deployment

The framework is currently undergoing evaluation by the National Weather Service, with plans for a phased operational deployment beginning in late 2026. The first phase will see the AI system running in parallel with the existing National Water Model, allowing forecasters to compare outputs and build familiarity with the new system.

If the parallel testing phase is successful, the AI framework could become a primary forecasting tool by 2027, representing the most significant upgrade to the nation's flood prediction capabilities in over a decade.

The researchers emphasize that the AI framework is not intended to replace human forecasters but to augment their capabilities. The model handles the computationally intensive task of processing vast amounts of data and generating initial predictions, freeing forecasters to focus on the nuanced judgment calls that still require human expertise, such as evaluating the credibility of upstream observations and communicating risk to emergency managers and the public.

Climate Adaptation Potential

Looking further ahead, the AI framework's data-driven approach may prove particularly valuable as climate change continues to alter historical flood patterns. Traditional models calibrated on past observations may become increasingly unreliable as the climate shifts into uncharted territory. The AI framework, with its ability to continuously learn from new data, could adapt to changing conditions more rapidly than physics-based models that require manual recalibration.

In a world where extreme precipitation events are becoming both more frequent and more intense, the ability to predict floods accurately and quickly is not just a technical achievement. It is a matter of public safety and national resilience.